Fertiliser use in NZ

Since modern agricultural practice began, New Zealand farmers have been supplementing the soil's natural nutrient level with fertiliser to improve the land's production potential. See below for the latest data on the use and management of fertiliser in New Zealand.

Jump to:

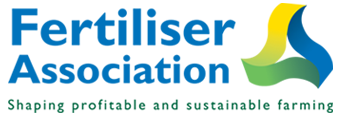

Nitrogen use

Most nitrogen used in New Zealand is applied to dairy and cropping farms and a limited number of drystock farms. Urea is the dominant form of nitrogen fertiliser used. Prior to the 1990s, pastoral systems were almost solely reliant on clover to fix nitrogen. The figure below is in thousand tonnes of nitrogen.

Data source: Fertiliser Association

Overall, nitrogen use has increased over time due to the intensification of dairy farm systems in combination with an increased area in dairying. However, production methods have improved and the emphasis on environmental accountability is increasing. This has led to marked improvements in production per unit of nitrogen applied. Improvements in efficient use of fertiliser and other nutrient sources are likely to continue as research and development evolves. Between 2020 and 2023 there has been a 22% drop in nitrogen use.

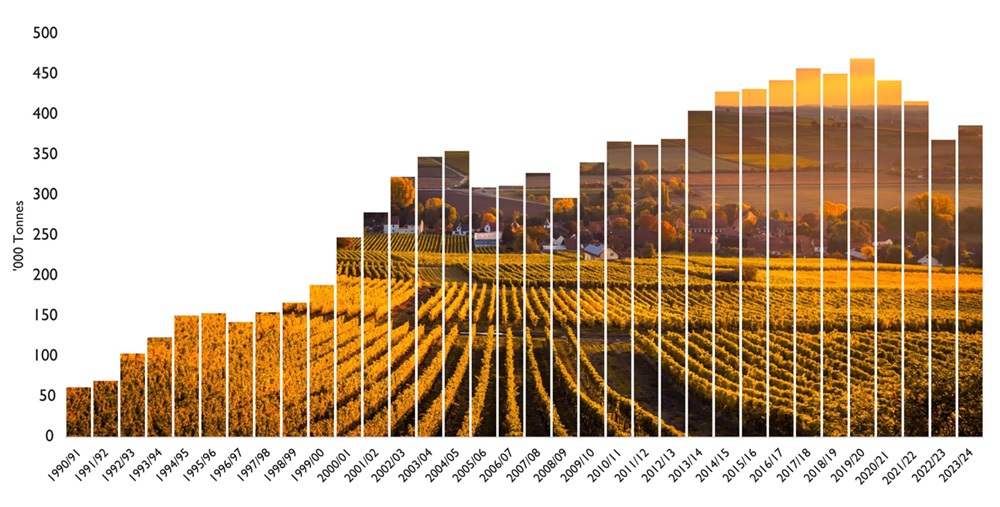

Phosphorus use

New Zealand pastoral soils are naturally low in phosphorus and sulphur. Both these elements are provided by superphosphate fertiliser. New Zealand began importing phosphate fertiliser in 1867, with its first shipment of guano from the Pacific Islands. Superphosphate manufacturing commenced near Dunedin in 1881. Today, it is manufactured at five sites. The figure below is in thousand tonnes of phosphorus.

Data source: Fertiliser Association

Phosphorus use has declined since a peak from 2003 to 2005. This reflects the impact of a significant price rise in 2008/09 and economic pressures, particularly for sheep and beef farmers receiving lower returns at that time. The moderate usage also reflects the increasing focus on nutrient budgets. This involves using fertiliser more strategically than ever before, as farmers learn how to maintain productivity while using less.

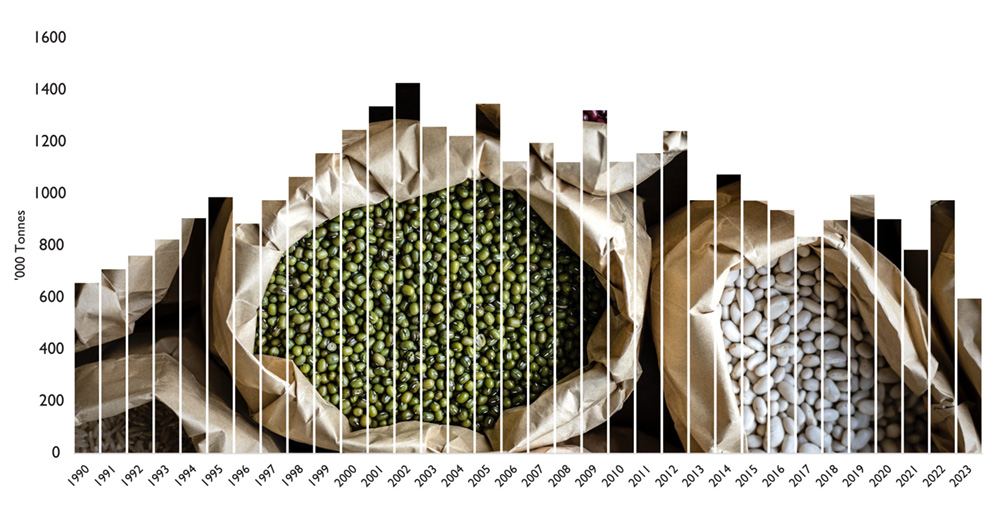

Potassium use

Potassium is an essential nutrient for keeping pastures productive and maintaining their legume component. Potassium fertiliser is required to replace the losses that occur through livestock urine and dung, leaching, transport to farm tracks and yards, and sale of meat, milk and wool. The figure below is in thousand tonnes of potassium.

Data source: Fertiliser Association

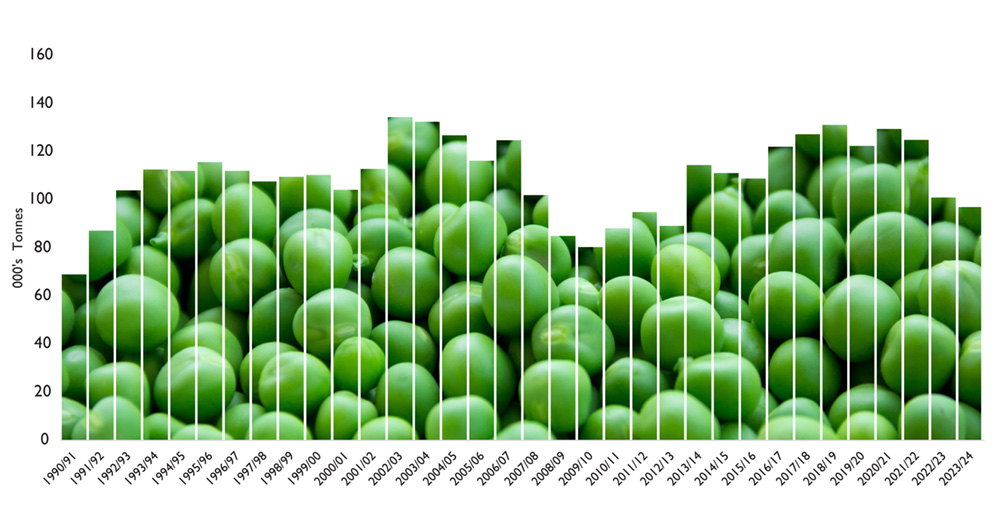

Lime use

Data source: Ministry for the Environment, National Greenhouse Gas Inventory

Leaching, decomposing organic matter, erosion and plant uptake of essential nutrients can all contribute to the acidification of soils over time. Soil pH affects nutrient availability. Plants are able to use nutrients more efficiently in soils with the right pH. Applying lime or dolomite restores the soil pH. Legumes are especially sensitive to low pH and growth will decline as the soil becomes more acidic. This graph shows how lime use has declined significantly since a peak in 2002. The figures above are in thousand tonnes product.

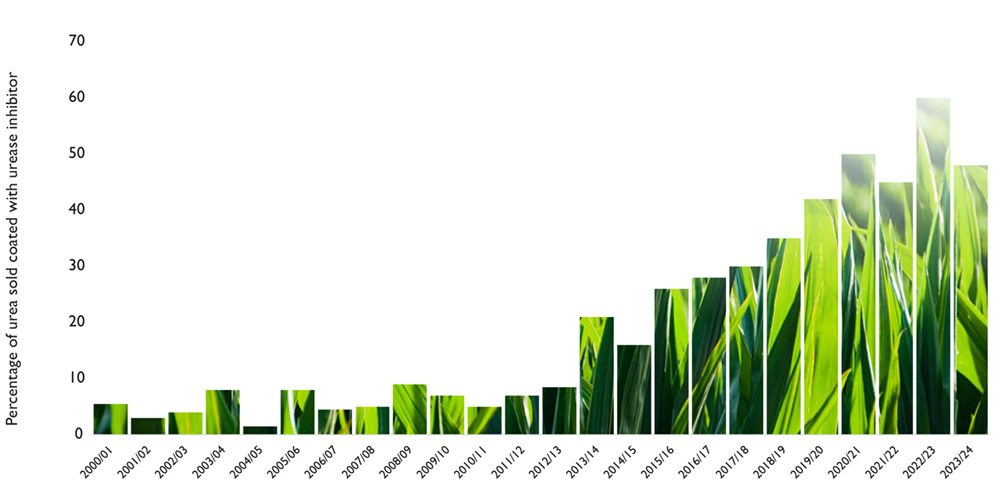

Percentage of urea coated with urease inhibitor

Data source: Fertiliser Association

As urea dissolves, it goes through a number of chemical changes. The conversion of urea to the ammonium and then nitrate forms of nitrogen, can result in significant losses to the atmosphere as ammonia. Urea fertiliser coated with a urease inhibitor has been sold in New Zealand since 2001. Use has increased significantly over the past decade, with 60% of urea sold coated with urease inhibitor in 2023. This is a positive step for the environment as it reduces volatilisation losses of ammonia from urea use, maximises nitrogen available for uptake and contributes to mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

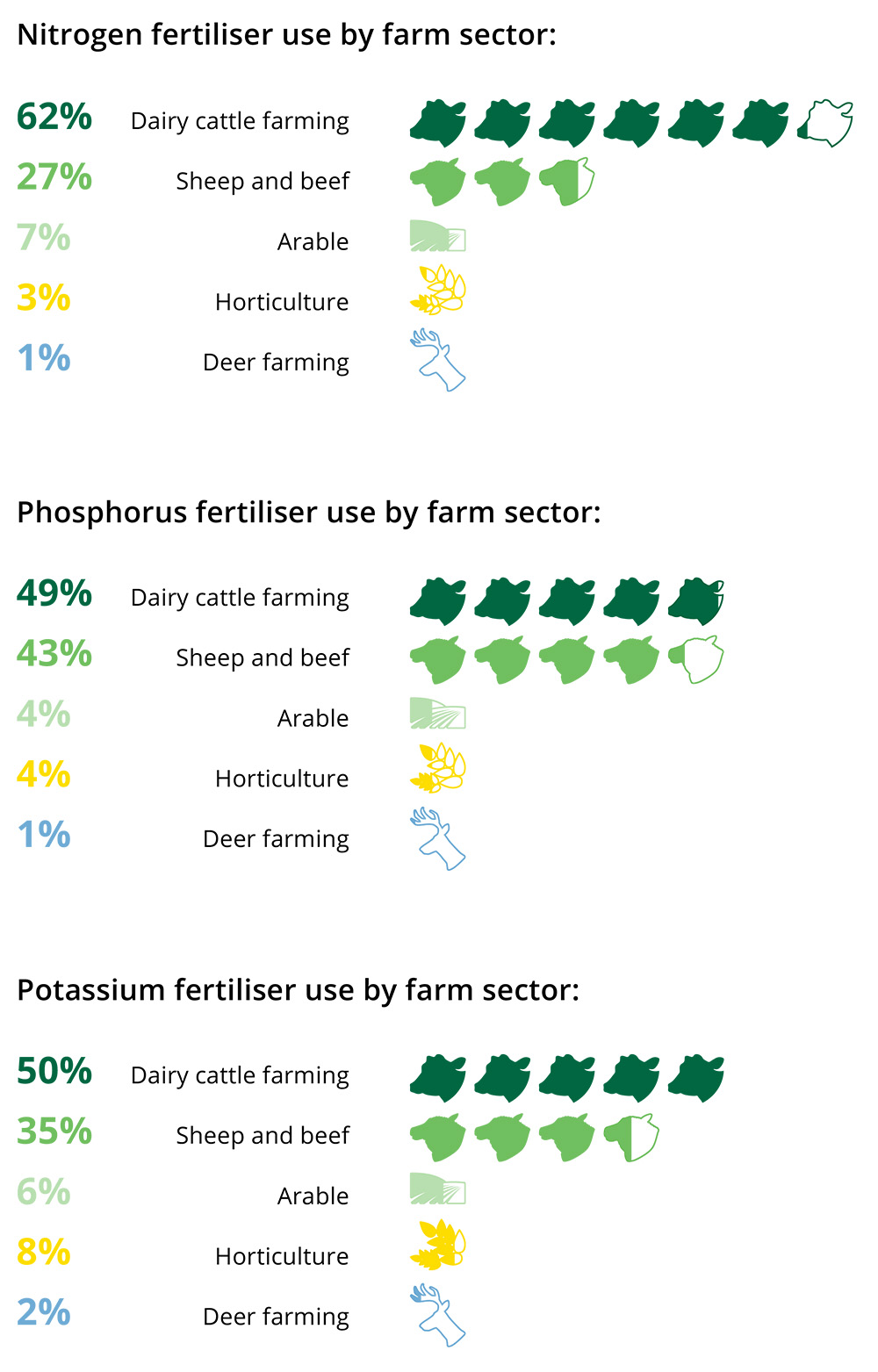

Fertiliser use by farm system

Nitrogen is mainly used on dairy and cropping farms, and a small number of dry stock properties. Phosphate is used across all farm systems.

Data source: Source: Agric Production Census 2022

National emissions from nitrogen fertiliser in kt CO2-eq

Data source: Nitrogen fertiliser: based on industry estimates using New Zealand’s National Inventory emission factors

In 2023, greenhouse gas emissions associated with nitrogen fertiliser represented approximately 2.7% of all agricultural emissions.

(Ref page 199, NZ National Inventory 1990-2023, Vol 1, Chapters 1-10)

Overall nitrogen fertiliser use has dropped since 2020, resulting in a 22% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions associated with nitrogen fertiliser.

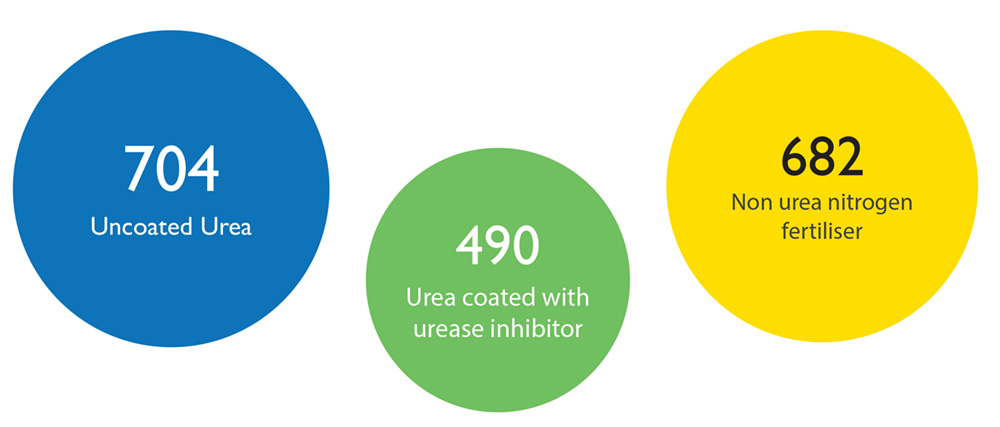

Source: Fertiliser Association for N, ( 2023 values)

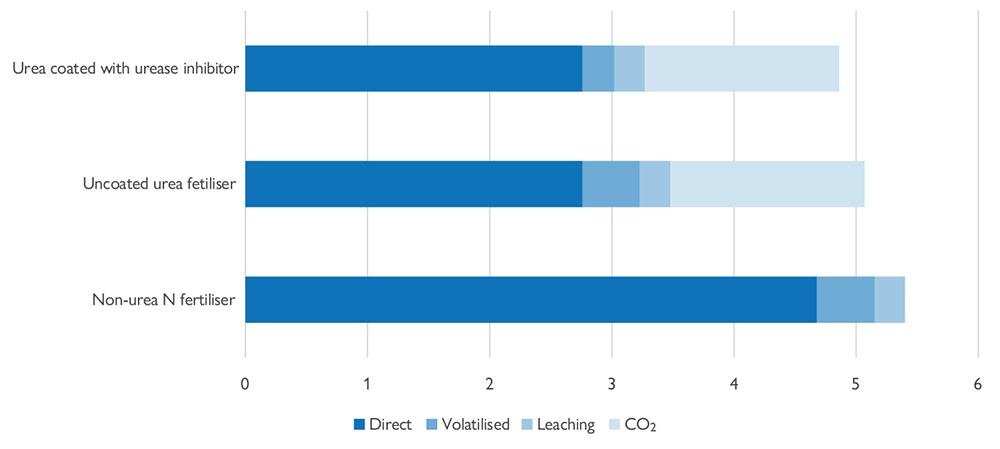

Emissions per tonne of fertiliser nitrogen in tonnes of CO2-eq

Data source: Ministry for Primary Industries

The New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory calculates the emissions for different forms of nitrogen fertiliser based on agreed emission factors. The primary source of emissions is nitrous oxide lost directly following application. A small proportion of the nitrogen applied is volatilised to the atmosphere as indirect losses by denitrification. Further losses occur following leaching. The use of urea-based fertiliser also results in direct CO2 emissions.

Nutrient management

21,054 farms now have formal nutrient planning documentation in place - either a nutrient budget, a nutrient management plan, a Good Agricultural Practice (GAP), or other farm nutrient planning documents.

Data source: Stats NZ 2022 Agricultural Census

Data Source: NMACP Ltd

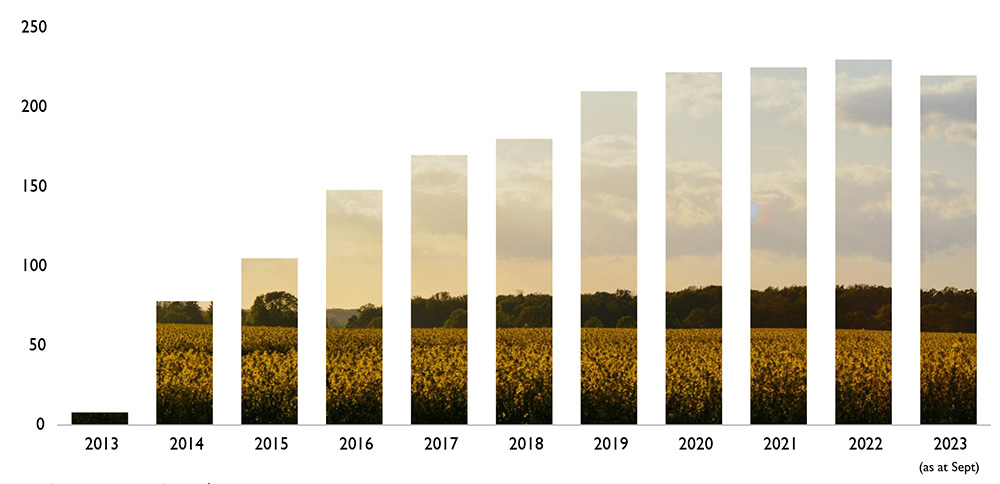

The Nutrient Management Adviser Certification Programme (NMACP) is managed by the primary sector as an industry-wide certification programme targeted at those who provide nutrient management advice to New Zealand farmers.

NMACP aims to ensure farmers get nutrient management advice of the highest standard. Relevant qualifications and experience are essential. Once certified, advisers need to undertake continuing professional development each year. As at September 2023, 220 advisers were certified.

The certification programme is financially supported by the Fertiliser Association, Beef + Lamb NZ and DairyNZ and the management board includes representatives from NZIPIM.

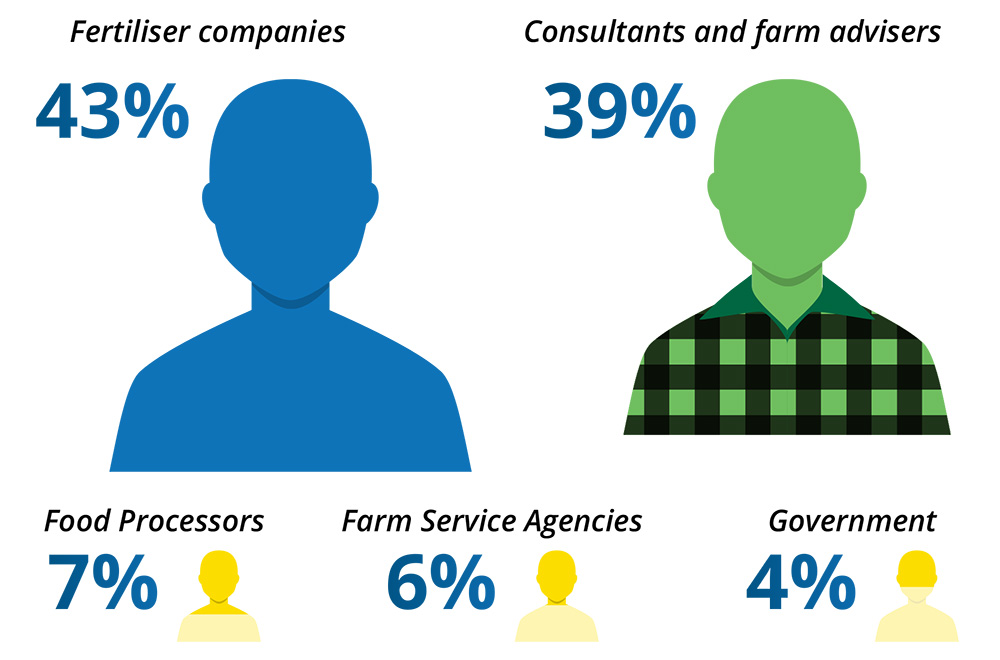

Where do certified advisers work?

Certified advisers work in a wide range of organisations. These include fertiliser companies, consultancy firms,central government, regional councils, food processing companies, farm advisory organisations and universities.

Certified advisers are expected to demonstrate their understanding of nutrient cycling in agricultural systems and use the right information to provide sound farm system advice. Auditing was introduced to the Nutrient Management Certification Programme in 2017 as part of building the value of the certification programme. Advisers are required to submit reports for auditing as a requirement of continuing professional development.

Fertiliser quality

The Fertmark programme was established by the Fertiliser Quality Council in 1992 to give New Zealand farmers confidence in the quality of fertilisers and the associated advertising. Products receive the Fertmark Quality Tick if they meet independently audited quality standards presented in "The Code of Practice for the Sale of Fertiliser in New Zealand".

Data source: Fertiliser Quality Council

Managing contaminants

Fertilisers are essential for viable, economic production in agricultural and horticultural farms. Phosphate fertilisers are derived from phosphate rock, which contains trace levels of a range of elements. Some trace elements like zinc are essential for the health of animals and plants. Others are not. If they occur at excessive levels in the soils, they can have an adverse impact on the environment or human health.

Global and New Zealand research indicates that cadmium and fluorine are the elements in phosphate rock most likely to accumulate in agricultural soils over many years of phosphate fertiliser use. There are no indications for concern from the levels of contaminants currently in New Zealand soil.

.jpg)

Cadmium concentration in weekly samples of fertiliser for dispatch, collected from the main manufacturing locations. The graph summarises 9,310 samples, showing monthly median values, the overall median, the 90% confidence band, and the voluntary limit of 280 mg/kg P.

Data: Ballance Agri-Nutrients & Ravensdown, FQC QCONZ data

Independent auditing monitors the cadmium content of fertiliser against a voluntary limit for cadmium. Monitoring demonstrates that the industry is operating at levels much better than the voluntary limit.

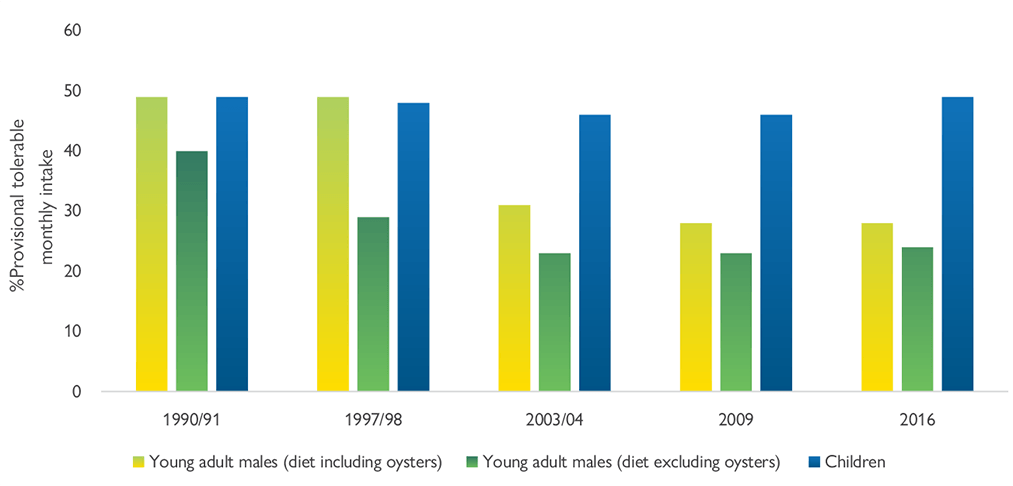

Dietary exposure to cadmium as measured in MPI's Total Diet Study

The New Zealand Total Diet Study is a nationwide survey of foods sold in New Zealand. The study is undertaken by MPI. The study aims to assess New Zealanders' exposure to certain food contaminants, based on a typical diet. The 2016 study involved the analysis of 1056 food samples, which were assessed for a range of potential contaminants.

Data source: MPI Total Diet Study 2016

Results show dietary cadmium exposures have largely remained consistent over time, and the chart reflects the observation that children typically have a higher food intake per kg body weight than adults. There is no evidence of increased risk, with cadmium levels in food remaining well below World Health Organisation recommended guidelines.